In my very first year of teaching, I was assigned to teach Christian Life Education and one of the stories in the textbook was Shel Silverstein’s “The Giving Tree.” It was a very simple story that featured a tree who loved a boy so much that it gave away everything from its fruits to its branches to its trunk until there wasn’t any more to give but a place to rest. And yet the oddly repetitive line throughout the story was this:

“And the tree was happy.”

Taught in the context of religion, it was easy to use the metaphor for God’s unending generosity and blessings despite man’s self-centeredness and shallowness. The Giving Tree was a constant, a home that the boy could always return to when it was in need, a steady source of support and love.

I’d like to think of the Ateneo as somewhat like the Giving Tree. And that is said from years of walking its halls, from the Jesuit-named buildings of what was then known as the College of Arts and Sciences, to the Ateneo Grade School, the Ateneo High School, and finally the Ateneo Senior High School.

If these halls could only speak then they would share how several men and women devoted their lives in forming generations of Ateneans, in the Ignatian tradition of being persons-for-others. The values were not just written on memos, they were living testaments who modeled these in their day-to-day interactions with the students.

Mr. Roberto Selorio Sr. was one of the very first people who mentored me in the Ateneo Grade School. During the in-service sessions, he would not just lecture how discipline was expected in the classroom, he actually made us go through the experience, so we wouldn’t forget. In a demo class composed of us as the students, he checked if the noise level was too much, and called out those who were not sitting straight (“Legs for sale!), and made us pass our papers in the correct way.

Mang Bert took charge of the daily flag ceremony, where he would drill the sponsoring class in the right way of respecting the flag, forming the lines and leading the entire school in prayer and in patriotism. He said to us young teachers, “Do not smile until December.” I didn’t think he was serious until I discovered the hard way he was actually right. There was wisdom in keeping a professional distance from the students. He was about to retire that year and yet he very willingly took on the responsibility so that we would learn rigor and firmness.

Mrs. Araceli Abando was one other mentor I can single out. She was my grade level coordinator when I taught grade 6. Like Mang Bert, Mrs. A was a stern taskmaster. She instilled in me that the students deserved fairness at all times, even in the way they were assessed. Taking one look at my record book, I remember her saying, “Your quizzes are too easy! You have so many students with grades in the 90s.” What I thought would be something I would be praised for turned out to be a flaw, something I needed to address in order to enforce a higher standard and a more realistic learning curve. She woke up teachers who were napping during their free time, saying they were being paid for every hour and so we should be attending to school-related matters at all times.

And yet, she was mother to us all, the one who listened to all our angsty complaints, and made sure we felt cared for at all times. The term “cariño brutal” suited her. My lesson plans were full of red corrections and my classes were observed so many times, but through all that I emerged a better teacher. Personal care meant consistency in duty, so we would not in any way or form, shortchange our students.

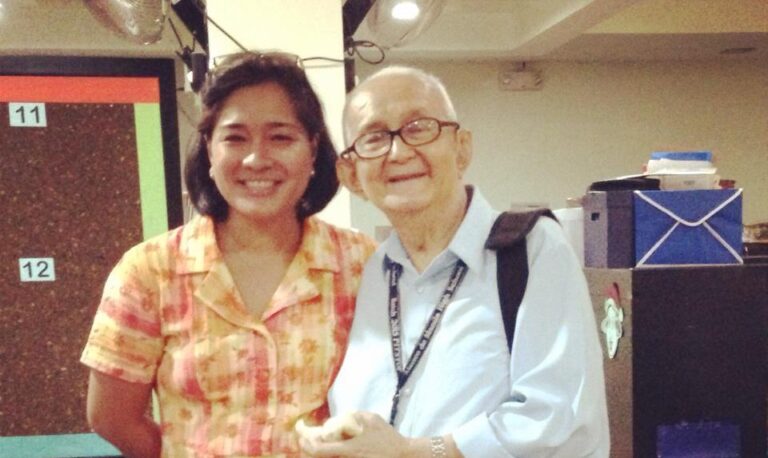

When I moved to the high school, of course the legend, Mr. Onofre Pagsanghan was still in residence, and it was an honor to be in the same subject area as he was, and I have pictures to prove that he would still do his visual aids in the old style of Manila paper and marker pens even as we were already using Powerpoint presentations. His longevity in the profession, and his love for the Ateneo was still readily apparent even after decades of staying in the high school.

Much has been said about Mr. Pagsi but it was the simple conversations with him that I valued the most. In one such conversation, he talked about what kept him going and that was knowing his “why.” He was approaching his nineties then but it was still very clear to him what the mission was: to sustain our students’ faith in God and make sure that AMDG was not just some scribble they would casually write in their test papers, but an honest to goodness offering of all their daily efforts for the greater glory of God.

The last educator I’d like to pay tribute to was a very jovial lady named Ms. Grace Valerie Almagro. The English subject area in old AHS was composed of many different personalities, mostly very expressive and opinionated, and so it couldn’t be helped that views would clash and meetings always had the potential to be explosive. People wouldn’t hesitate to give their two cents’ worth on any concern and usually the back and forth seemed unending.

This type of discussion would continue until Ma’am Val raised her hand to give her own take on the issue at hand. I don’t know if it was just me, but that was usually the cue. Whatever she said would be the last comment. Because her comments were very well thought of, given only after listening to everyone, and in her wisdom, deciding on what was the best course of action. She was also very gracious and generous in sharing her own resources and materials which was very life-giving to a clueless newbie like me. In my short time with her, I learned to further open my mind and heart to differing opinions, especially as I was away from my comfort zone. I also learned to reach out to people who may be also struggling.

They are all retired now, no longer on campus, but somehow they had passed on the spirit that has kept this school faithful to what it stands for, to the countless students who had been under their tutelage, to the even more numerous teachers who were forever inspired by their example, this writer included. There are jokes about people being institutions themselves, being “haligi na ng Ateneo,” but honestly, in this world today characterized by fickleness and impermanence, their perseverance in carrying out their duty brought to the fore the characteristics that defined Jesuit education.

Magis. Cura personalis. Finding God in all things. Non multa sed multum. A faith that does justice. Persons for and with others.

They did not just teach these. They lived and breathed these.

They are just some of the Giving Trees on this Giving Hill. And unlike the allegorical tree in the storybook, the giving is reciprocated, because in some way or another, it does not go unnoticed. The seeds they have sown have traveled far and wide and many have found fertile ground. For as long as people remember them and what they stood for, they will live forever.

We stand on the shoulders of giants on this hill. May we honor them. May we be them.

A lifelong fan of anything Jesuit being a second generation employee of the Ateneo de Manila University, Sansan Borja grew up staying at the Rizal Library and the Loyola House of Studies where her parents worked. She entered as a student in 1988 at the then College of Arts and Sciences and never left. She is currently the principal of the Ateneo De Manila Senior High School.