What is the role of a university in the modern world? Is it merely to produce knowledge by means of research to boost its academic performance? Is the university separate from the society where it is located? Is the university a neutral institution? Answers to these significant questions depend on how one defines what a university is. The identity of the university ideally defines the vision, mission, and kind of education it will provide. Thus, there is a need to strengthen the university’s identity by constantly drawing inspiration from it and if necessary, to deepen and update it in the light of contemporary concerns.

The Society of Jesus is well known for its commitment to education. According to estimates, there are over 3,000 Jesuit educational institutions around the world. Around two hundred of these are university-level institutions. What they have in common is their unique identity as both Catholic and Jesuit educational institutions. To avoid confusion and misinterpretations, we should be mindful that the terms “Catholic” and “Jesuit” are never mutually exclusive. Rather, both are intertwined and enrich each other. To be a Catholic and Jesuit university entails embodying Catholic teaching and Jesuit spirituality.

The superior general of the Society of Jesus, Fr. Arturo Sosa, SJ, in his book interview titled Walking with Ignatius, reiterates the essential mission of Jesuits in the complex domain of the university: “University is an exciting place that mirrors the complexity of society. In universities, one is confronted by many different ideas. The aim is to create knowledge, discuss ideas, and think about the future. The Society of Jesus cannot cease to be a presence in this arena.” (emphasis mine) He then cites Fr. Pedro Arrupe, SJ to emphasize the value of educating inclusively, similar in spirit with catholicity, in the Jesuit tradition: “We are committed to educating any class of person, without distinction. It cannot be otherwise, because the educational apostolate (just as every other apostolate of the Society) bears the indelible Ignatian imprint of universality.”

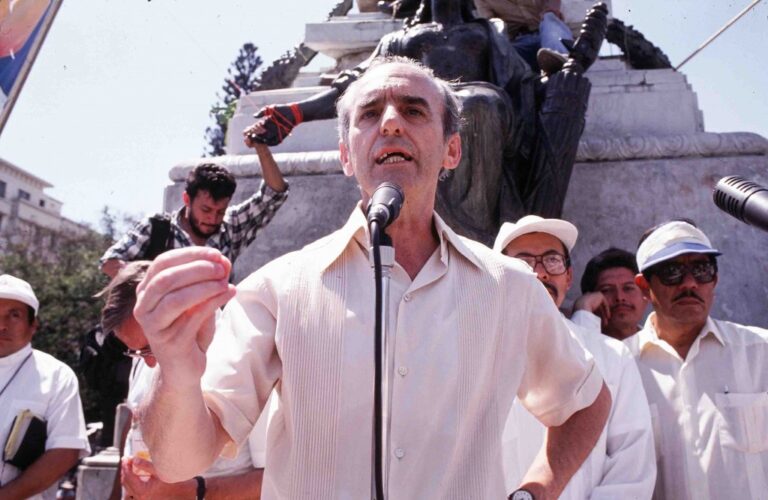

If the university allows intellectual engagements and debates considering the plurality of perspectives and ideas in dealing with a variety of issues involving society and should educate both the rich and the poor, what should be the stand of a Catholic and Jesuit university in society in general? Must it be neutral or must it take sides with the oppressed? In responding to this multi-layered question, I will turn to the example of a Jesuit theologian and former president of the University of Central America (UCA) in San Salvador, Fr. Ignacio Ellacuria, SJ. Tragically, Ellacuria with his five Jesuit companions and their cook and teenage daughter were brutally assassinated by members of a US-trained counter-insurgency battalion of the Salvadoran army on November 16, 1989 at the UCA.

The Jesuit theologian Jon Sobrino, SJ, who was spared since he was out of the country when the horrible incident occurred, remembers their legacy in redefining the role of a university: “They let us know that university knowledge can and must be placed at the service of the poor. And they left us with the proof that, in doing so, the university itself can grow.” Indeed, their witness of defending the victims of social injustice reveals to us what a university inspired by Christian values and immersed in historical realities look like in practice. “They put into practice an idea of a Christian university for our times in the Third World,” says Sobrino.

In a 1975 essay titled “Is a Different Kind of University Possible?”, Ellacuria envisioned the university as “committed to opposing an unjust society and building a new one” by “its very structure and proper role as a university.” In other words, it is a socially engaged university serving as “the critical and creative consciousness of the national reality.” As a liberation theologian, Ellacuria shuns the dichotomy between God’s transcendence and history – a harmful dualism plaguing our understanding of Christianity and spirituality. A university faithful to its Christian roots must not escape from the world and avoid confronting societal crises.

Years later in his commencement address at Santa Clara University in June 1982, Ellacuria spoke about the task of a Christian university. For him, the Christian university not only “deals with culture” and “with knowledge, the use of the intellect” since “it must (also) be concerned with the social reality—precisely because a university is inescapably a social force: it must transform and enlighten the society in which it lives.” There is no room for neutrality in Ellacuria’s understanding of a Catholic and Jesuit university. Knowledge and action are united. In the words of the Jesuit theologian Roger Haight, SJ, “The critical mental abilities of human beings have the role of directing human behavior. If knowing were not oriented to human action, it is hard to imagine what else it would be for.”

Critics would point out that this approach politicizes the university, departs from magisterial authority, and is mainly swayed by Marxist ideology. Against these criticisms, let me cite Pope John Paul II who in his apostolic constitution on Catholic universities titled Ex Corde Ecclesiae categorically proclaims the social responsibility of a Christian university: “The Christian spirit of service to others for the promotion of social justice is of particular importance for each Catholic University, to be shared by its teachers and developed in its students. The Church is firmly committed to the integral growth of all men and women.” (no. 34) Ellacuria’s convictions are solidly based on the long tradition of Catholic social teaching, especially the famous phrase “preferential option for the poor.” The Pope even encourages the Christian university to speak truth to power: “If need be, a Catholic University must have the courage to speak uncomfortable truths which do not please public opinion, but which are necessary to safeguard the authentic good of society,” (no. 32) reminiscent of the lives and fate of the Jesuit martyrs of UCA.

Ellacuria genuinely walked his talk. Under his prophetic leadership “the UCA transformed in the 1970s and 80s into one of the most outspoken critics of the brutal military regimes that governed El Salvador and of the social, political, and economic structures that undergirded the massive inequality that characterized Salvadoran society,” explains Michael Lee. In his distinctive vision, the heart of the mission of a Catholic and Jesuit university is what he calls “social projection.” Social projection transforms teaching and research by decentering the university, orienting its pedagogy towards the peripheries where people are wounded by social structures. UCA’s social projection produced institutes such as the Human Rights Institute (IDHUCA), the Institute of Public Opinion (IUDOP), and the UCA’s Seminar on National Reality.

Catholic and Jesuit universities have so much to learn from the praxis of Ignacio Ellacuria, SJ and his companions of the UCA. But, it should be noted that UCA responded to its particular social location and to its reading of the signs of the times. Each Catholic and Jesuit university has its own context and circumstances. Hence, careful discernment is required for the university to incarnate its social projection wherever it finds itself. While academic freedom and inclusive education remain hallmarks of university education, these elements must not compromise the Jesuit non-negotiable element of “faith that does justice.”

—

Kevin Stephon R. Centeno, SJ, a Jesuit scholastic from the Philippines, obtained his AB Philosophy from St. Augustine Seminary, Calapan City. He joined the Society of Jesus on August 1, 2021.