ANNEX B

JESUITS IN MINDANAO

PART I: The First Jesuits in Mindanao, Before the Suppression

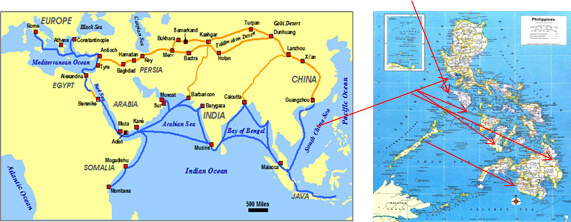

1. 1596: Very First Expedition. Juan del Campo and Bro. Gaspar joined the expedition led by Captain Esteban Rodriguez de Figueroa to Rio Grande (Pulangi River) to conquer Mindanao and to reduce the Muslims to submission to Spanish rule. Within a year, Gomes returned to Manila to accompany Figueroa’s corpse and Del Campo died while chaplain of the Spanish forces in Mindanao. Del Campo was only 30 years old.

2. 1597-1614: Second Expedition. Valerio de Ledesma and Fr. Manuel Martinez successfully inaugurated the first church in Mindanao in Butuan on 8 September 1597. They baptized 800 catechumens within a year. [1]

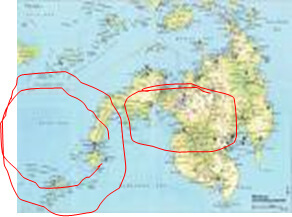

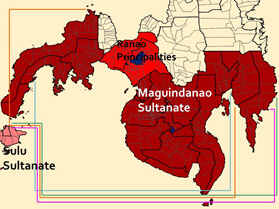

3. 1624-1768: Second Return to Mindanao. The Jesuits were back again in Mindanao in 1624 when the Spanish colonial government divided the island into two mission territories: The western part (Sulu, Zamboanga and Cotabato ) to the Jesuits and the eastern part (Northern Mindanao, Surigao, and Agusan) to the Recollects. The Jesuits started the Dapitan mission in 1631 followed by the Zamboanga mission in 1633.

4. 1600’s: Jesuits as Peace Ambassadors. In 1605, Fr. Melchor Hurtado—himself captured in a slave raid— was sent as a peace envoy by the Spanish colonial government. The Muslims provisionally accepted. In 1640, Pedro Gutierrez, negotiated for the freedom of slaves with Sultan Kudarat, Lord of Rio Grande, and with Rajah Bungsu of Jolo. Fr. Alejandro Lopez continued Hurtado’s work in breaking peace in Rio Grande, Sulu, and Buayan where he was successful in gaining truces from them.

5. 1640’s: Martyrs in Northwestern Mindanao. The Jesuits suffered martyrdom in their work with the Subanons and Muslims: Francisco Mendoza between Iligan and Marawi in 1642 and Fr. Francesco Palliola in Ponot in 1648.

6. 1663-1718: 55-Year Absence from Zamboanga. Because of the threat of attacks by the Chinese invader Koxinga, Zamboanga and southern Mindanao was abandoned in 1663. But during this time, the Jesuits continued their dangerous work with the Subanons and Muslims in northwestern Mindanao despite the past experience of martyrdoms.

7. 1718: Return to Zamboanga and into Jolo and Tamontaka. When they returned to Zamboanga in 1718, the Jesuits continued their pursuit of peace with the Muslims.

The Jesuits also defended the natives from the abuses of some opportunistic encomenderos and sent the sons of some native Christians to the Jesuit college in Cebu, Collegio de San Ildefonso. In 1614, the Jesuits left their only mission area on the island, leaving the Church’s mission on the island to the RECOLLECTS who back in 1609 had started a mission in Tandag, Surigao.

They were welcomed to Tamontaka and Jolo for a while but had to abandon the mission posts when it became clear that the warm welcome given them was a deception.

8. 1754: Armed Mission in Iligan. Francisco Ducos, a missionary in Iligan, did not shy away from military strategies. In 1754, he led an attack on Panguil Bay, which the Muslims used as a base for their violent pillaging. Ducos got control of the base, burned various towns, and managed to capture 170 ships. He was made commander of the Spanish fleet of Iligan, and was able to defeat the raiders several times.

9. 1768: The Execution of the Royal Order Suppressing the Society of Jesus in the Philippines. When the royal order of suppression by King Charles III arrived in Manila on 17 May 1768, the Jesuits had to leave Mindanao. The following were already considered parishes under their care: Zamboanga, Dapitan, Bayog, Lubungan, Dipolog, Iligan, Initao, Ilaya, and Misamis. The Recollects and the diocesan clergy of Cebu took over these vacated parishes.

PART II: Return to Mindanao, After the Restoration

16. 1832-1857: The Repeated Requests for Jesuits to Return to the Philippines after the Restoration. In 1832, Bishop Santos Gomez Marañon, O.S.A. of Cebu requested King Ferdinand VII of Spain for Jesuits in his diocese; but the Jesuits did not have enough personnel. In 1857 Bishop Romualdo Jimeno Ballesteros, O.P. of Cebu made another request to Queen Isabella II for Jesuits to minister to the districts of Bislig, Davao, Pollok and the provinces of Zamboanga and Basilan Island. This time, the Jesuits were ready.

17. 1859: Arrival in Manila. On 13 June 1859, 10 Jesuits (6 priests and 4 brothers) led by Fr. Jose Fernandez Cuevas arrived in Manila. Cuevas immediately made arrangements to take over part of Mindanao. However, the residents of Manila asked them to set up a school (which is Ateneo de Manila University today). The following year, the Jesuits would attempt to fulfill their mission to Mindanao.

From their headquarters in Zamboanga, the Jesuits looked after the missions of Tamontaka and Jolo. In 1746, Fr. Francisco Zassi, the Rector of Zambaoanga, accompanied by Fr. Sebastian Ignacio de Arcada and Major Tomas de Arrivillaga, brought letters of friendship from King Philip V of Spain to the sultans of Tamontaka and Jolo. The Jesuit ambassadors were given every honor upon their arrival in the sultanates and were allowed to set up missions there: Fr. Juan Angeles and Fr. Josef Wilhelm were sent to establish a permanent mission in Jolo and Fr. Juan Moreno and Fr. Sebastian Ignacio de Arcada were sent to found a mission in Tamontaka.

Moreno and de Arcada had to leave Tamontaka though as they soon learned that the warm welcome given them was a deception since the Maguindanaos merely wanted to seize the ships sent from Zamboanga. The mission to Jolo met a more tragic end. Sultan Mohammed Ali-Mudin claimed that he wanted to be a Christian and so he went to Manila to be baptized in April 1750. In truth he only wanted to obtain advantages from the government in Manila. This scheme was foiled and he was captured on his way back to Jolo. In retaliation, his brother led the Joloanos to a ferocious war against the Christians, killing many including the Jesuit missionaries to Jolo, Angeles and Wilhelm.

18. 1860: The Reconnaissance Visit to Mindanao. The Queen decreed on 30 July 1860 that the Jesuits “will engage in the spiritual care of the island and will replace the present parish priests [the Recollects]”. In the same year, Cuevas was finally able to go to Mindanao in 1860 to prepare the way for the Jesuits to return to the island.

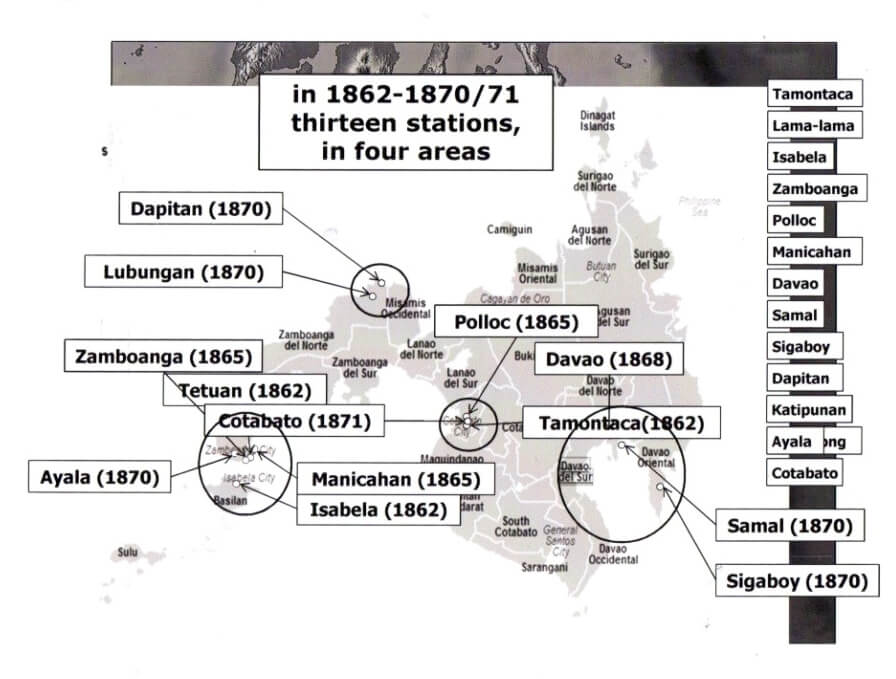

19. 1861-2: The Strategic Entry into Northern Mindanao. Cuevas returned from his reconnaissance in 1861 and suggested that Jesuits begin their ministry with the already Christianized areas in northern Mindanao. Four Jesuits led by Fr. Ignacio Guerrico arrived in the island in January 1862. They started their mission at the mouth of Pulangi, where military advances were taking place for the effective possession of the region. [3]

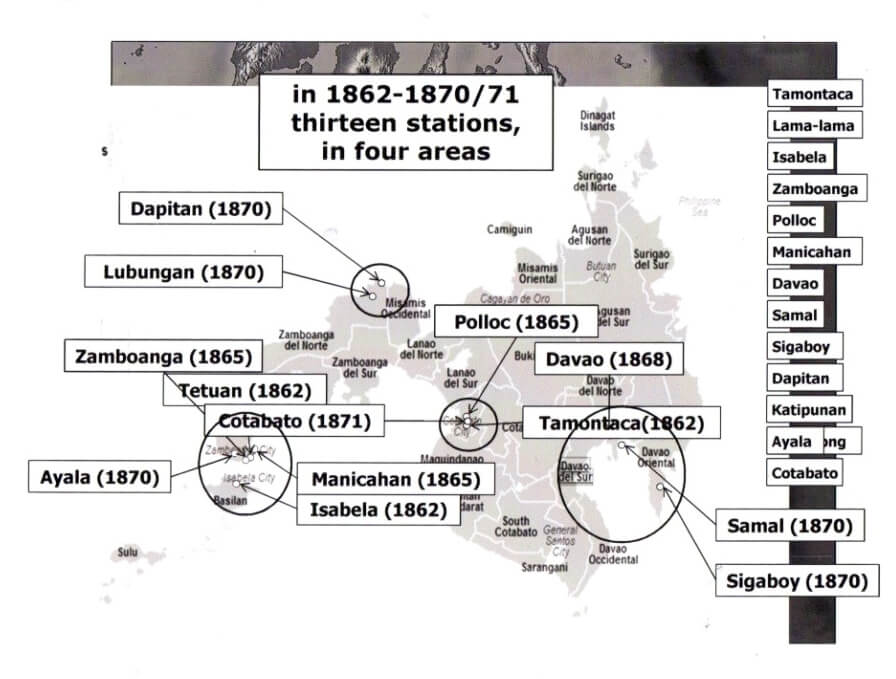

20. 1865 and Following: The Mission to the Rest of Mindano. Upon the foundation of the Diocese of Jaro in 1865, the districts in the south such as Zamboanga and Basilan, Jolo, Cotabato, and Davao were formally assigned to the Jesuits. Later on, the districts in the north and east, which still belonged to the Diocese of Cebu: Dapitan, Misamis, Surigao, and Bislig (Caraga) were added. Only Cagayan remained under the Recollects until the 19th century. [4]

It was hoped that the evangelization of Mindanao could start with the gentle and receptive Tirurays who were in constant contact with Maguindanaos. The work with the Tirurays would hopefully pave the way for the conversion of the dominant Muslim tribe. Following the establishment of the first mission of the restored Society of Jesus in Tamontaka along the Rio Grande, another Jesuit, Fr. Ramon Barua, took over Tetuan parish in November of the same year.

[1] The Challenges of the Mission: Dispersed Populace, Muslim Attacks, Diseases. A renewed focus on inculturation, working for peace, and – in the words of the great missionary Fr. Saturnino Urios – “humanizing the people before Christianizing them” marked the Jesuit mission in the 19th century. But, like the Jesuits of the old Society, they faced tremendous challenges. In the first place, there were no real homes and towns work in; the scattered living of the populace being mainly a result of the threat of raids. In the second place, the Jesuits themselves were constantly harassed by hostile Muslims and the different indigenous peoples. Infidels from the mountains would constantly swoop down on the Jesuit missions resulting in the loss of not only property but even the lives of the missionaries. The Jesuits would have to ask help from the government’s military forces for protection. But, in some cases, as what happened in Bukidon, the Jesuits asked for arms to form their own militias. In addition, unsanitary conditions placed them under constant threat of widespread sicknesses, making it doubly difficult for them to set up communitie.

The Mindanao Jesuits met these challenges with missionary zeal and creativity. As their brethren in other parts of the world had done, the first missionaries in Mindanao realized they had to bring people together in order to form them in the faith. In Caraga, Fr. Pablo Pastells organized nomadic tribes into settlements. This he did by first marking out the central plaza, streets, chapel, municipal hall, and schools. The natives were taught how to build houses with walls, windows, and rooms. He was able to carry this out much more easily because he relied on the traditional datus and tribal leaders to bring people together and convince them to live in permanent communities. Fr. Saturnino Urios followed a much more simple principle. Aside from exploring the Rio Grande, forging peace between warring tribes, and founding new towns, especially in Agusan, he believed that in order to evangelize one had to exercise much patience, charity, and courage. He went through great pains to show the local people the advantages of stable community life and then he made them respect the principle of authority. Fr. Jaime Plana realized that the Mamanua people would only be willing to embrace the Gospel if their most elementary needs of food and clothing were met, so he found ways to provide these. He was also tireless in gathering them back into the settlements when they went back to their nomadic ways, as was the case many times.

Language and Inaccessibility. There was also the problem of language. In some areas each tribe had a different language, e.g. in Davao, the Bagobos, the Tagacaolos, and the Mandayas each had a different language. And then there was the problem of isolation or inaccessibility. Some missions in Mindanao were also isolated, with very limited communication with the outside world. In the Caraga mission for example, three to five months would pass before any ship passed by.

Contrary Culural Beliefs and Practices. There were also some practices and customs which the faith deemed immoral but were so much part of the way of local way of life. Even in the flourishing communities such as the Agusan mission, it would not be surprising to find Christian communities disappear soon after the missionaries leave due to deeply ingrained, non-Christian beliefs. The Jesuits had to likewise be careful about condemning people publicly or too strongly because of the risk of retaliation, which could cost the missionaries their lives. As parish priest in Zamboanga in 1865, Fr. Francisco Javier Martin Luengo decided against open confrontation with public immorality. Instead he patiently discussed the dangers of practices such as gambling to each family by visiting them at their homes. To combat the bagani code, practiced along the east coast, Fr. Domingo Bove taught sedentary agriculture alongside human life.

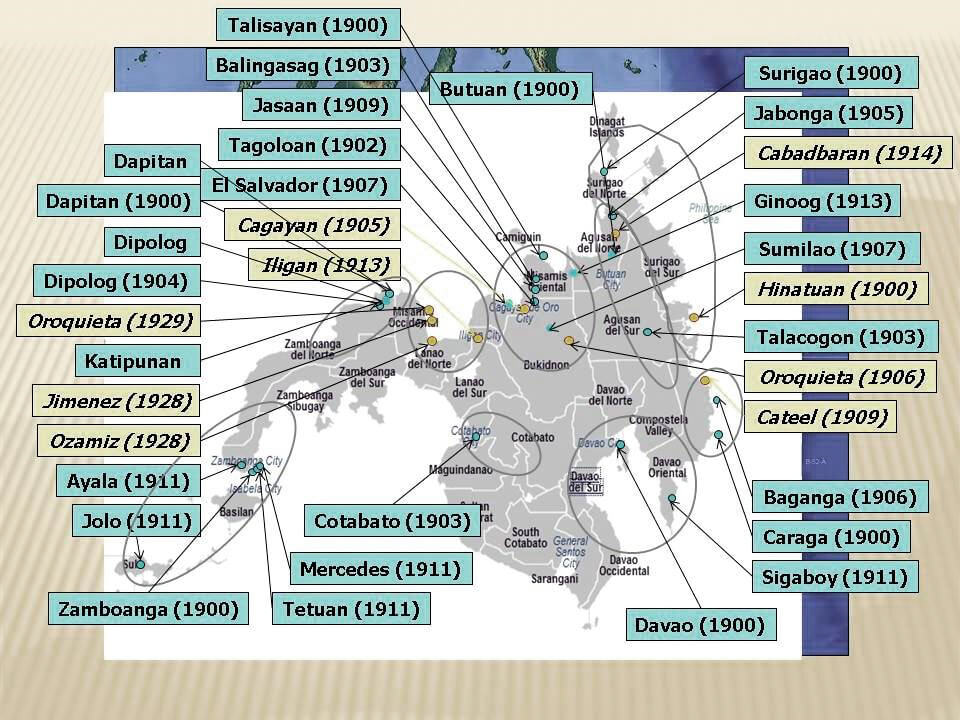

21. In the 1860’s, the Jesuit mission in Mindanao entered the regions of Zamboanga, Cotabato, and Davao

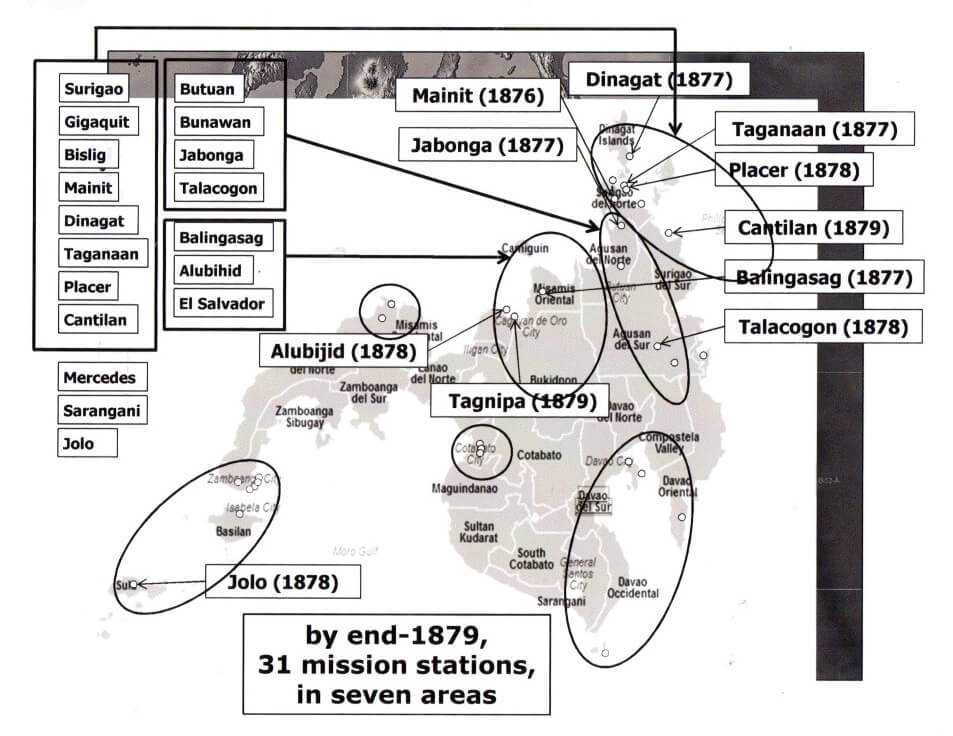

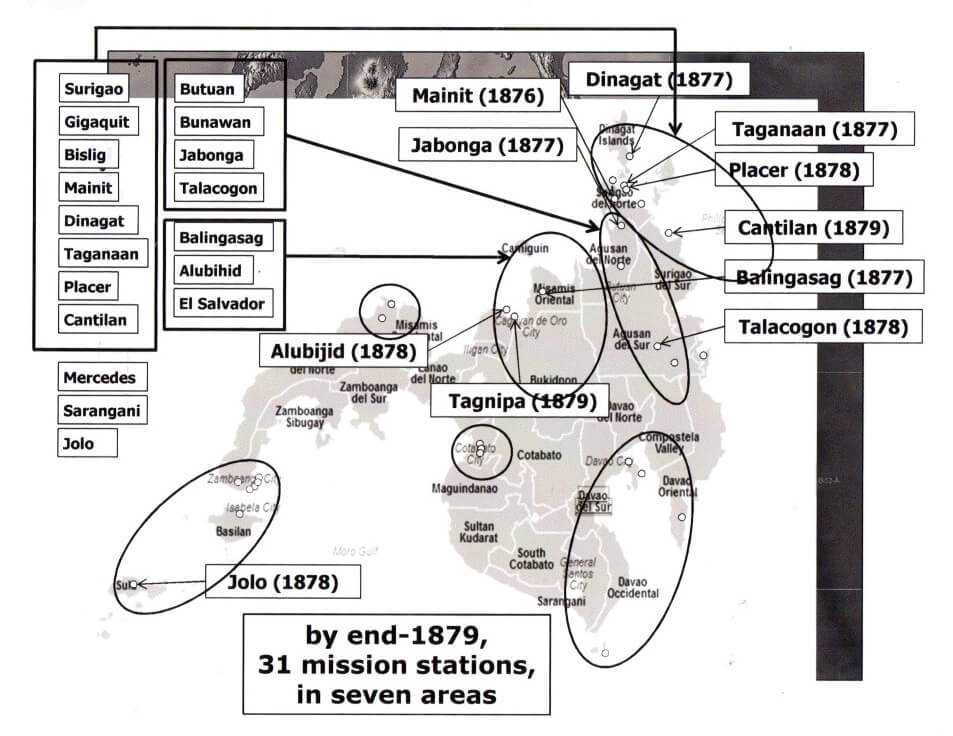

22. In the 1870’s, the mission had spread out to four more regions: Surigao, Agusan, Misamis, and Saranggani

22. In the 1870’s, the mission had spread out to four more regions: Surigao, Agusan, Misamis, and Saranggani

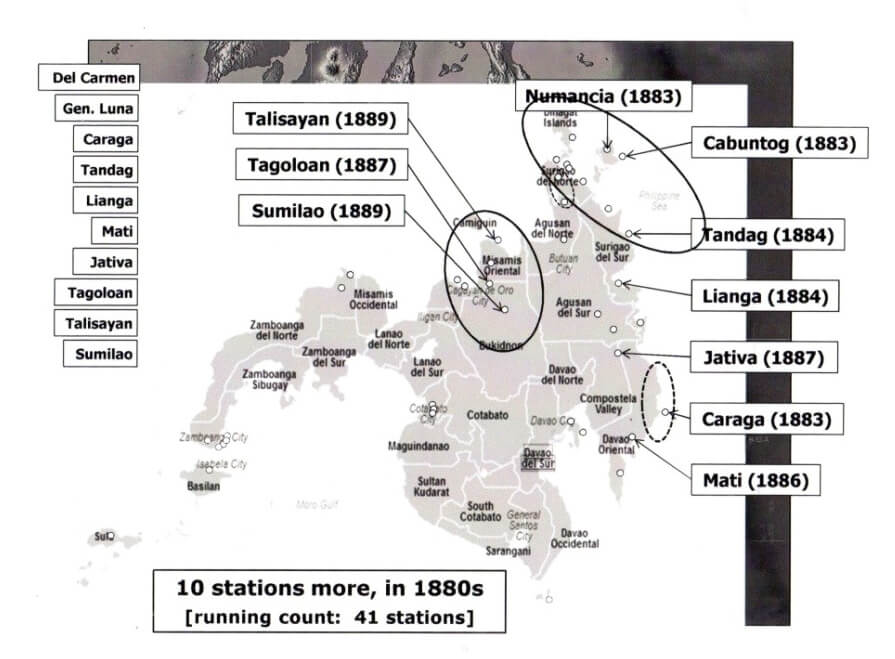

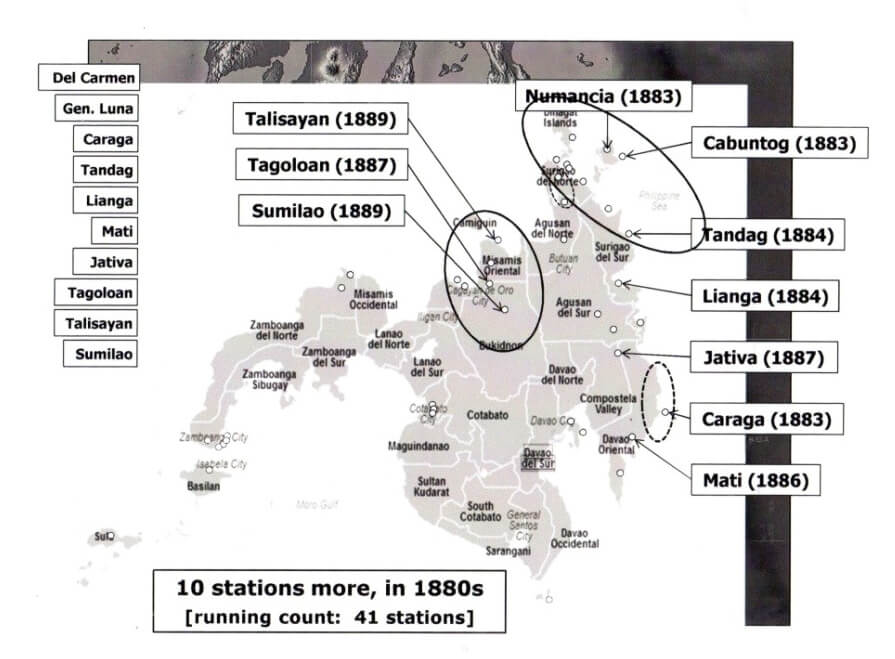

23. In the 1880’s, the mission opened up only one more region, that is Bukidnon, but the number of stations in the covered territory increased drastically.

23. In the 1880’s, the mission opened up only one more region, that is Bukidnon, but the number of stations in the covered territory increased drastically.

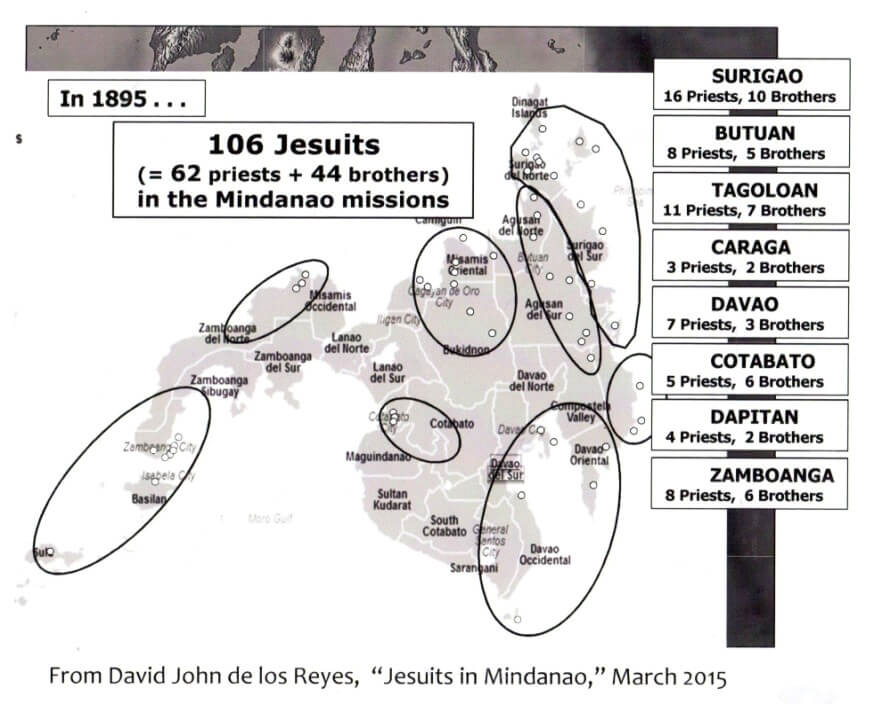

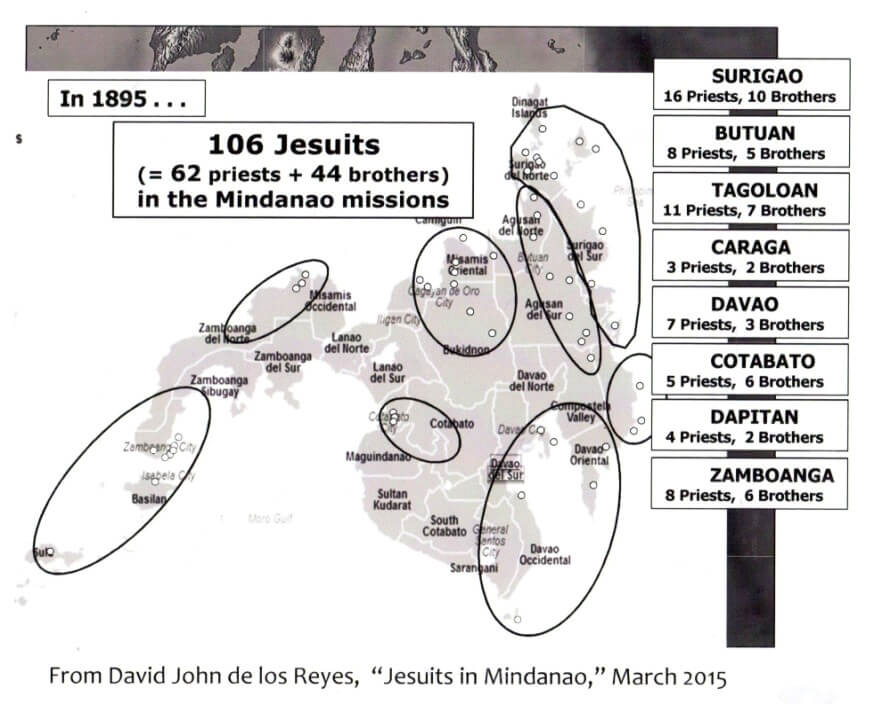

24. By 1895, there were 106 Jesuits in Mindanao,62 priests and 44 brothers, in eight regions of the island, manning ___ mission stations.

24. By 1895, there were 106 Jesuits in Mindanao,62 priests and 44 brothers, in eight regions of the island, manning ___ mission stations.

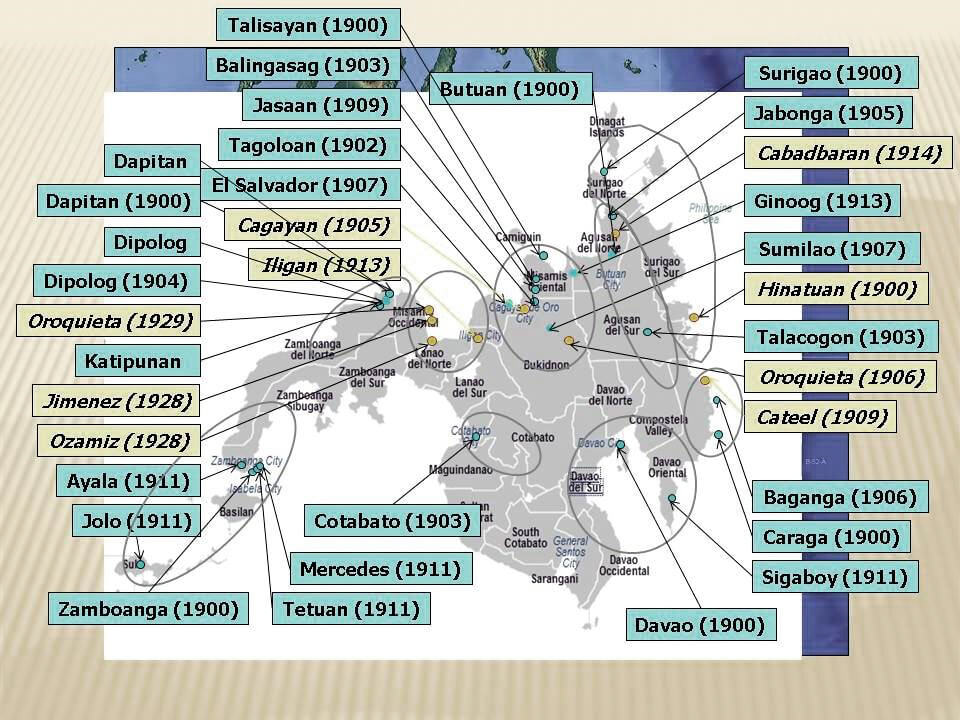

25. The Time of the Philippine Revolution. Although the people perceived the Jesuits as different from the friars, it still happened that all the Jesuits were recalled to Manila by 1898. By the year 1900, however, they were back in Mindanao. They returned to empty reductions with barely a hint of previous Catholic influence. Reopening the mission in Mindanao was marked with several new challenges: the lack of funds because there was no more patronato real to draw from, the lack of manpower because there were no more new arrivals of Spanish Jesuits and those around were aging, the threats due to the anti-Spanish, nationalist sentiments, and the perceived protestant threat represented by the establishment of Silliman University in 1901.

25. The Time of the Philippine Revolution. Although the people perceived the Jesuits as different from the friars, it still happened that all the Jesuits were recalled to Manila by 1898. By the year 1900, however, they were back in Mindanao. They returned to empty reductions with barely a hint of previous Catholic influence. Reopening the mission in Mindanao was marked with several new challenges: the lack of funds because there was no more patronato real to draw from, the lack of manpower because there were no more new arrivals of Spanish Jesuits and those around were aging, the threats due to the anti-Spanish, nationalist sentiments, and the perceived protestant threat represented by the establishment of Silliman University in 1901.

Since the aggression towards the Catholic Church was directed towards the friar orders and because the Philippine revolution centered on Manila, the Jesuit mission in Mindanao proceeded with little interruption, at least in the beginning of the revolution. In one instance, when Spanish officials gave up their posts to Filipinos in Surigao after independence was declared in 1898, Fr. Alberto Masóliver was elected chairman of the province junta. In Agusan, the people asked Fr. Francisco Nebot which flag should be raised while waiting for the official one. Nebot suggested the papal flag, and the people agreed.

[1] Pillaging marked their properties; even chapel fixtures were not spared. Upon their return, they also saw that Protestantism had taken root and some of their chape

ls were taken over by the Aglipayans and other religious groups.

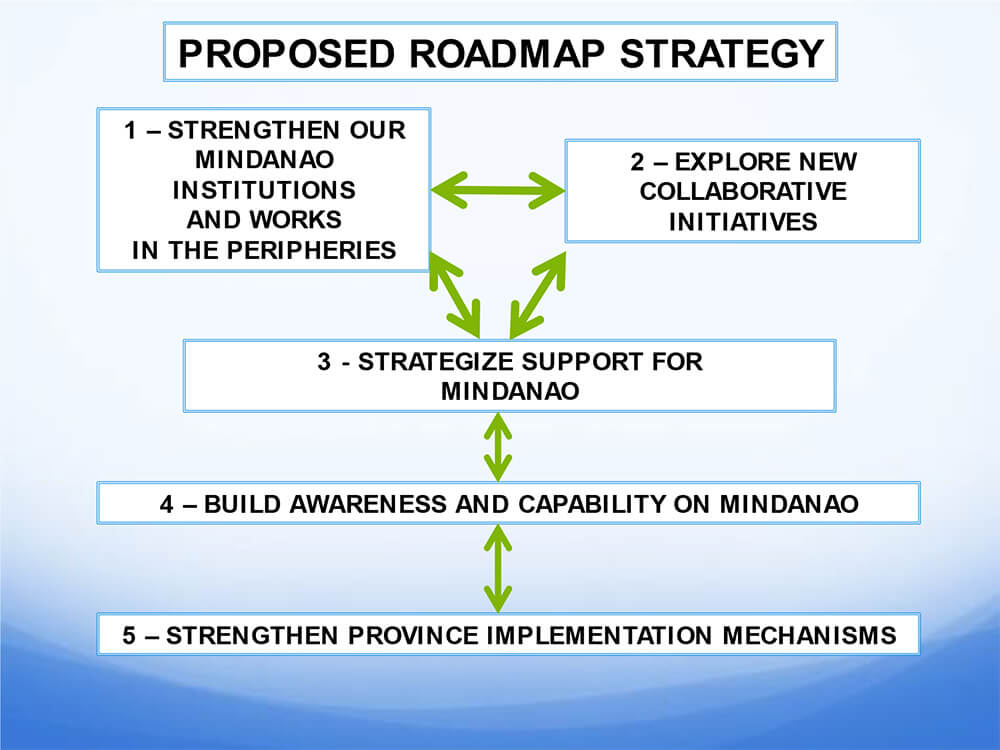

26. A 20th Century Roadmap for the Mindanao Mission. To address these challenges, the superior Pio Pi drafted a guide for superiors in Rome and Spain which covered the following: a) the protection of missionaries; b) more Jesuit missionaries, preferably Americans; c) the nomination of a bishop to Mindanao if possible a Jesuit; d) the establishment of a seminary; and e) the founding of schools apart from mission stations. Fr. Luis Adroer, Provincial of Aragon, emphasized in his response that the Jesuits focus on territories not yet Christianized. This meant the Jesuits should turn well-established missions to other priests..

27. Jesuit Manpower in Mindanao through the 20th Century From 1900 to 1921, the Spanish Jesuits held the fort waiting for the Americans who started taking over the stations in 1921. The turnover was completed in 1929. In the first 30 years of the century, the Jesuits were both reactivating and adding new stations.

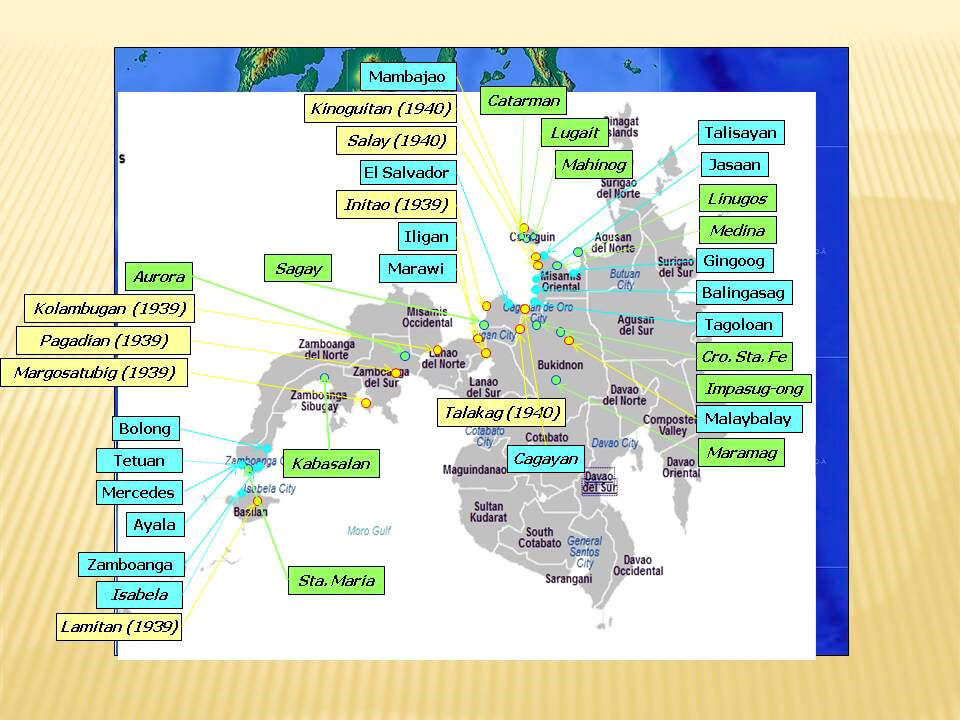

In the map above, the stations that are identified in italics are new stations, and the rest are reactivated statios.

In the map above, the stations that are identified in italics are new stations, and the rest are reactivated statios.

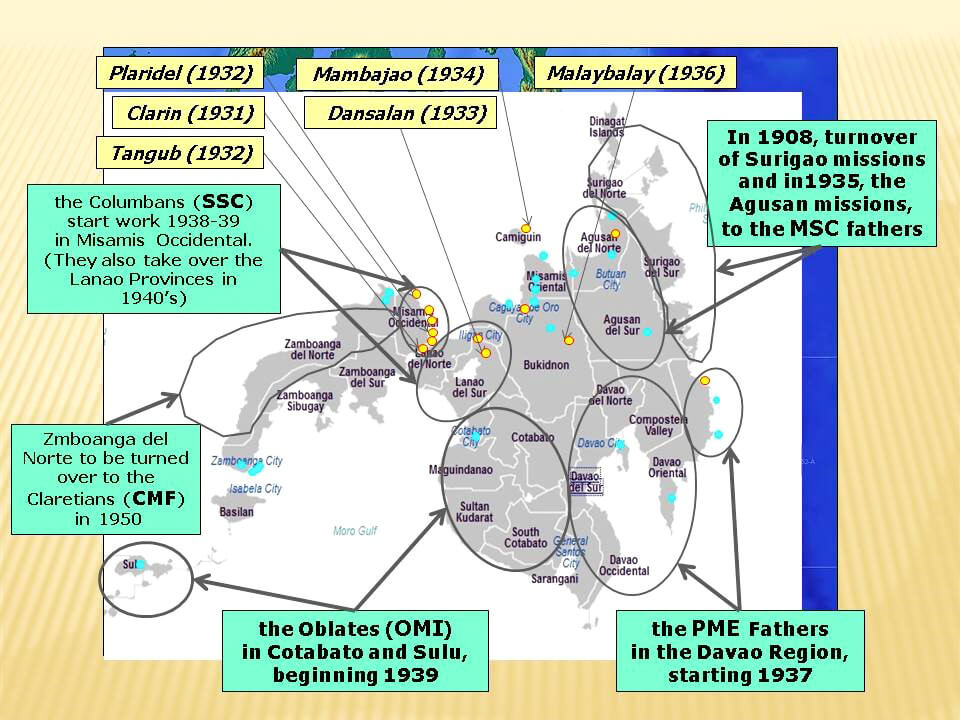

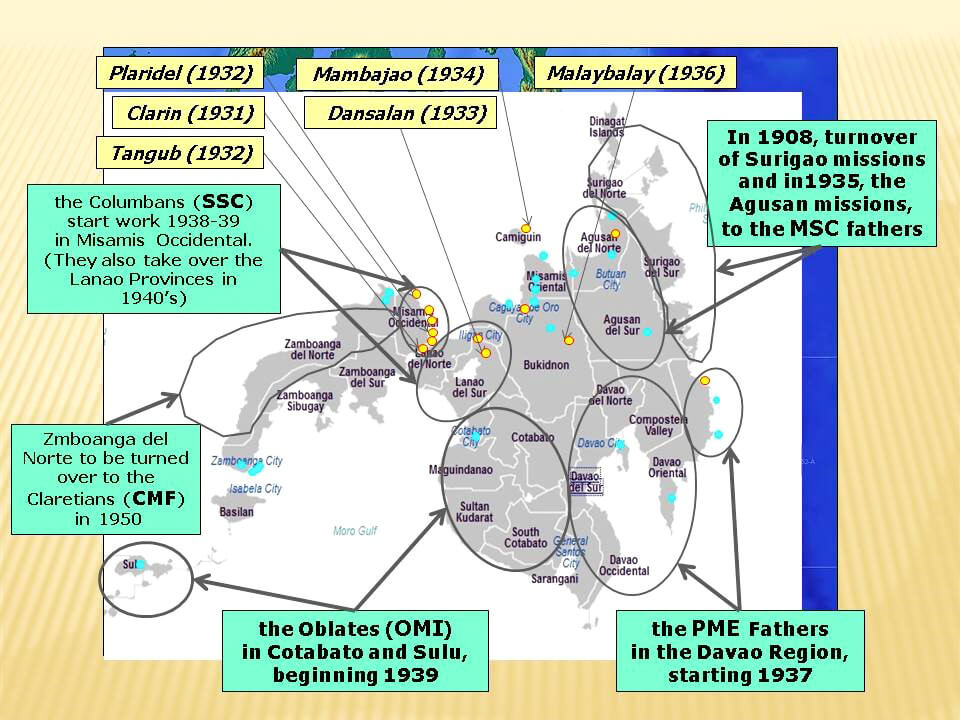

28. 1930’s: Simultaneous Movements of Additions and Turnovers. In the 1930’s, there was a series of turnovers of sub-regions of the island to other religious priests, while there was a continuation of new stations being set up in the regions still in the area of responsibility of the Jesuits. The Sacred Heart Missionaries had already taken over the Surigao region in 1908; they also took over the adjacent region of Agusan in 1935. In 1937, the Davao region was turned over to the P.M.E.’s, although the Jesuits would later return in 1948 to establish Ateneo de Davao. After adding three more stations in Misamis Occidental in the early thrities (Clarin-1931, Tangub-1932, Plaridel-1932), the Jesuits turned over Misamis Occidental to the Columban fathers (SSC) in 1938-9. The Oblates (O.M.I.) took over Cotabato and Sulu in 1939.

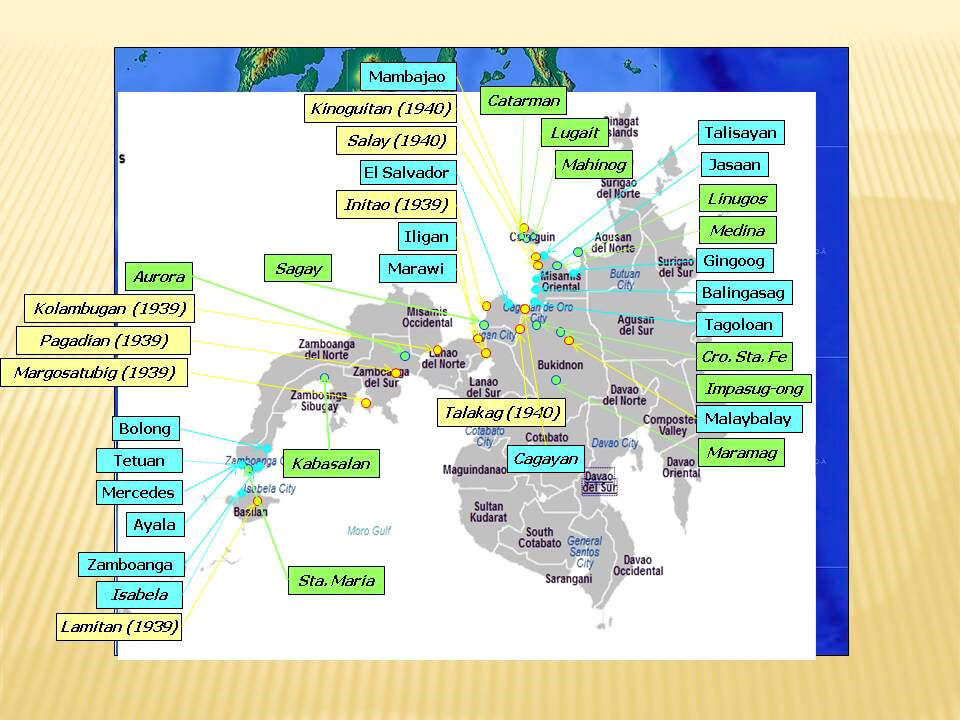

29. By 1939, the turnovers allow the Jesuits to concentrate their resources on the remaining areas of Basilan, the whole of the Zamboanga peninsula, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Bukidnon, and Misamis Oriental.

29. By 1939, the turnovers allow the Jesuits to concentrate their resources on the remaining areas of Basilan, the whole of the Zamboanga peninsula, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Bukidnon, and Misamis Oriental.

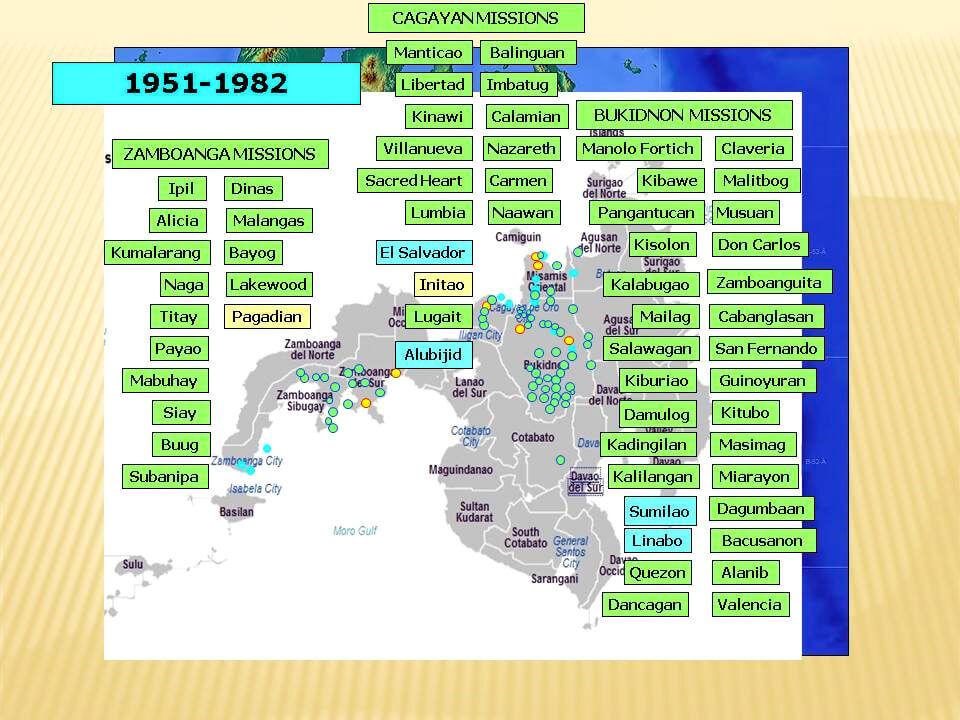

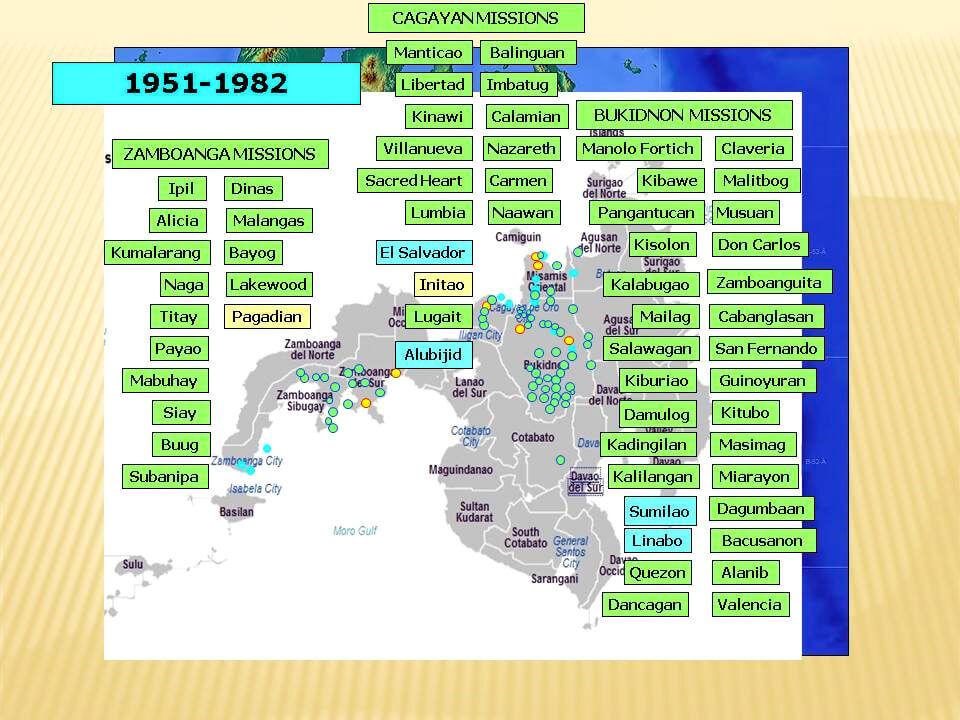

30. Mid-1940’s onwards. Beginning 1946, the Columbans began to take over the Lanao provinces. The Claretians (C.M.F.) began work in Zamboanga del Norte in 1950. The Archdioceses of Zamboanga and Cagayan de Oro were taking over the missions and parishes in their areas of responsibility. Misamis Oriental was turned over to the Archdiocese of Cagayan de Oro and Basilan to the Archdiocese of Zamboanga. This would leave just two mission areas for the Jesuits: Zamboanga del Sur and Bukidnon while maintaining their presence through the schools in Zamboanga City and Davao City. Once again the concentration of resources resulted in the rapid increase in mission stations in the remaining mission areas in the next decades.

30. Mid-1940’s onwards. Beginning 1946, the Columbans began to take over the Lanao provinces. The Claretians (C.M.F.) began work in Zamboanga del Norte in 1950. The Archdioceses of Zamboanga and Cagayan de Oro were taking over the missions and parishes in their areas of responsibility. Misamis Oriental was turned over to the Archdiocese of Cagayan de Oro and Basilan to the Archdiocese of Zamboanga. This would leave just two mission areas for the Jesuits: Zamboanga del Sur and Bukidnon while maintaining their presence through the schools in Zamboanga City and Davao City. Once again the concentration of resources resulted in the rapid increase in mission stations in the remaining mission areas in the next decades.

31. Pursuing the Pio Pi Roadmap.

31. Pursuing the Pio Pi Roadmap.

Deployment of More Missionaries. Apart from deploying the American Jesuits to Mindanao which was accomplished by 1929, the manpower problem in the Mindanao Mission was addressed by the turnovers to other religious congregations in the thirties and forties and later to the diocesan clergy. The arrival of the Chinese Delegation Jesuits in the 1950’s also significantly contributed to the continued rapid increase of mission stations.

Appointment of a Bishop. The development of the diocesan clergy may be said to have been in itself part of the roadmap as it was a natural consequence of the recommendation to establish a diocese with a Jesuit bishop. The recommendation to nominate a bishop in Mindanao was achieved in 1910 when Zamboanga became a diocese, although the bishop was not a Jesuit.. The following are ecclesiastical units that developed while under the Jesuit mission in Mindanao:

| 1910 Zamboanga Diocese |

1969 Malaybalay Prelature |

| 1933 Cagayan de Oro Diocese |

1976 Kidapawan Prelature |

| 1951 Zamboanga Archdiocese |

1979 Ipil Prelature |

| 1958 Cagayan de Oro Archdiocese |

1982 Malaybalay Diocese |

There are now a total of fifteen ecclesiastical units in Mindanao, one of which is under a Jesuit Archbishop: Archbishop Antonio Ledesma of the Archdiocese of Cagayan de Oro.

Mission to Previously Unchristianized Areas. The turnovers to other religious congregations and later to the diocesan clergy also made possible the fulfillment of the instruction from Fr. Adroer, Provincial of Aragon, which called on the Jesuits to move out to previously unchristianized areas. While turning over well-established missions, the Jesuits were continually moving out to new frontiers.

Founding Schools. Following on the recommendation of Fr. Pio Pi, schools were established with several of the mission stations. This continues today in the stations in Bukidnon Mission District. The Ateneo de Zamboanga was established in 1912, the Ateneo de Cagayan in 1933, and the Ateneo de Davao in 1948.

Founding a Seminary. The one thing among Fr. Pio Pi’s recommendations that the Jesuits did not accomplish themselves was the establishment of a seminary. However, the P.M.E. did establish the Regional Major Seminary in Davao in 1964. The Jesuits would then eventually figure significantly in the establishment of the inter-diocesan St. John Vianney Theological Seminary in 1985.

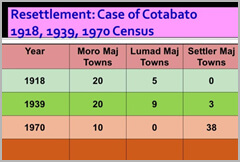

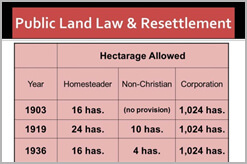

32. While Fr. Pio Pi’s Roadmap for the Mindanao Mission had the Christianization of Mindanao as a primary goal which was already largely accomplished in the first three quarters of the 20th Century, the Jesuit mission in Mindanao – over the last three decades at least – has been undergoing changes, rethinking, and re-direction. Many factors are responsible for these ongoing changes: The evolving understanding of the Society of Jesus of its mission since GC 32 to GC 35 that is of what it means to work for justice in an authentic living out of our faith; the realization of how the original inhabitants of Mindanao have been the victims of dispossession and minoritisation over the last century and how the Church may have inadvertently benefitted from this; the valuable insights provided by the social science and environmental science research on Mindanao, a lot of which comes from our own universities in the island; and the ever-increasing vulnerability of the island and its peoples to environmental, socio-economic, and political threats as well as the seemingly unresolvable armed conflicts.

Some responses since the 1970’s to the evolving demands of the mission in Mindanao include but are not limited to the following: the brave stand Jesuits took in defense of the people during the Martial Law years in the persons of Bishop Claver, Fr. Godofredo Alingal, Fr. Gus Nazaren, Fr. Cal Poulin, and Fr. Joseph Stoffel; the unprecedented attempts at dialogue such as Fr. Bill Kreutz’s invitation to Mr. Nur Misuari to ADZU, the development of social and cultural research in the persons of Fr. Madigan, Fr. Demetrio, Fr. Mike Bernad, and Fr. Albert Alejo; the work of the Environmental Science for Social Change based in Bendum; the development of IP schools by ADZU, ADDU, XU, and the Apo Pulamguwan Cultural Educational Center; the personal commitment of Frs. Matt Sanchez and Pedro Walpole to live with the lumads; the continuing works of the Bukidnon Mission District; the assignment of scholastics and new priests to Mindanao; and the various works, outreaches, research done by our universities and their centers and institutes too many to mention here.

33. With a renewed clarity of understanding, that our mission in Mindanao is not to be assessed by the Christianization of the island, but by the extent that the propagation of our faith there has planted and nurtured an authentic reconciliation among its peoples, between its peoples and its environment, and between its peoples and God, the Jesuit mission in Mindanao must continue with greater intensity, with a more profound understanding and analysis of the situation there, and with greater coordination to ensure our corporate efforts may indeed have the impact that we hope, imagine and intend to make.

22. In the 1870’s, the mission had spread out to four more regions: Surigao, Agusan, Misamis, and Saranggani

22. In the 1870’s, the mission had spread out to four more regions: Surigao, Agusan, Misamis, and Saranggani 23. In the 1880’s, the mission opened up only one more region, that is Bukidnon, but the number of stations in the covered territory increased drastically.

23. In the 1880’s, the mission opened up only one more region, that is Bukidnon, but the number of stations in the covered territory increased drastically. 24. By 1895, there were 106 Jesuits in Mindanao,62 priests and 44 brothers, in eight regions of the island, manning ___ mission stations.

24. By 1895, there were 106 Jesuits in Mindanao,62 priests and 44 brothers, in eight regions of the island, manning ___ mission stations. 25. The Time of the Philippine Revolution. Although the people perceived the Jesuits as different from the friars, it still happened that all the Jesuits were recalled to Manila by 1898. By the year 1900, however, they were back in Mindanao. They returned to empty reductions with barely a hint of previous Catholic influence. Reopening the mission in Mindanao was marked with several new challenges: the lack of funds because there was no more patronato real to draw from, the lack of manpower because there were no more new arrivals of Spanish Jesuits and those around were aging, the threats due to the anti-Spanish, nationalist sentiments, and the perceived protestant threat represented by the establishment of Silliman University in 1901.

25. The Time of the Philippine Revolution. Although the people perceived the Jesuits as different from the friars, it still happened that all the Jesuits were recalled to Manila by 1898. By the year 1900, however, they were back in Mindanao. They returned to empty reductions with barely a hint of previous Catholic influence. Reopening the mission in Mindanao was marked with several new challenges: the lack of funds because there was no more patronato real to draw from, the lack of manpower because there were no more new arrivals of Spanish Jesuits and those around were aging, the threats due to the anti-Spanish, nationalist sentiments, and the perceived protestant threat represented by the establishment of Silliman University in 1901. In the map above, the stations that are identified in italics are new stations, and the rest are reactivated statios.

In the map above, the stations that are identified in italics are new stations, and the rest are reactivated statios. 29. By 1939, the turnovers allow the Jesuits to concentrate their resources on the remaining areas of Basilan, the whole of the Zamboanga peninsula, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Bukidnon, and Misamis Oriental.

29. By 1939, the turnovers allow the Jesuits to concentrate their resources on the remaining areas of Basilan, the whole of the Zamboanga peninsula, Lanao del Norte, Lanao del Sur, Bukidnon, and Misamis Oriental. 30. Mid-1940’s onwards. Beginning 1946, the Columbans began to take over the Lanao provinces. The Claretians (C.M.F.) began work in Zamboanga del Norte in 1950. The Archdioceses of Zamboanga and Cagayan de Oro were taking over the missions and parishes in their areas of responsibility. Misamis Oriental was turned over to the Archdiocese of Cagayan de Oro and Basilan to the Archdiocese of Zamboanga. This would leave just two mission areas for the Jesuits: Zamboanga del Sur and Bukidnon while maintaining their presence through the schools in Zamboanga City and Davao City. Once again the concentration of resources resulted in the rapid increase in mission stations in the remaining mission areas in the next decades.

30. Mid-1940’s onwards. Beginning 1946, the Columbans began to take over the Lanao provinces. The Claretians (C.M.F.) began work in Zamboanga del Norte in 1950. The Archdioceses of Zamboanga and Cagayan de Oro were taking over the missions and parishes in their areas of responsibility. Misamis Oriental was turned over to the Archdiocese of Cagayan de Oro and Basilan to the Archdiocese of Zamboanga. This would leave just two mission areas for the Jesuits: Zamboanga del Sur and Bukidnon while maintaining their presence through the schools in Zamboanga City and Davao City. Once again the concentration of resources resulted in the rapid increase in mission stations in the remaining mission areas in the next decades. 31. Pursuing the Pio Pi Roadmap.

31. Pursuing the Pio Pi Roadmap.