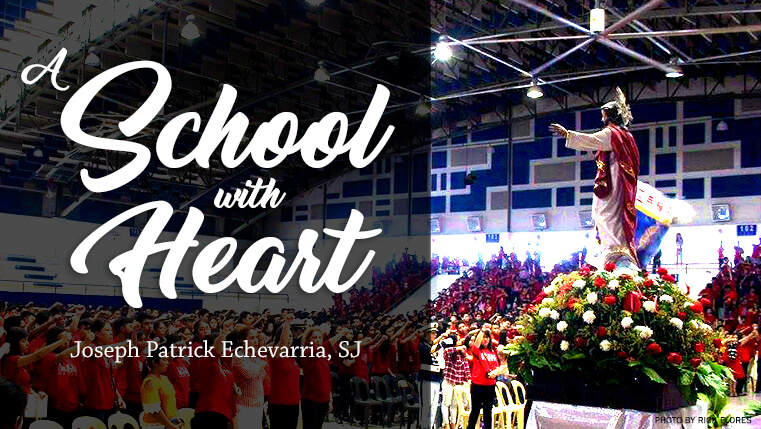

Joseph Patrick Echevarria, SJ

“When you join Sacred Heart: our goal is not just education but formation;

it’s not just a job but a vocation.” –

Overheard during the Orientation for New Faculty and Staff

When Father Manny called them last, I thought he made a mistake.

But then he stood his ground, placed his hands behind him, and paused. There was no mistake. The school’s president wanted to make an important point with everyone in the assembly that morning. The chatter in the arena died down as the summoned students slowly walked onto the stage, accompanied by their teacher. Father Manny met them at the center and gently shook the hand of each one and asked them to stand beside him.

Then he turned to face all the students, teachers, and parents present, and announced, “Lastly, I am proud to recognize these students. In the recent Cebu STEM Festival, during the robotics competition, an opposing team accidentally dropped their kit and spilled the components across the floor. The contest was under time pressure. But our students stopped what they were doing and helped the other team pick up the pieces. Their teacher did not tell them to help the other team. They just did. Our students displayed character. And for this: to me, they are already champions.”

Applause erupted and Father President beamed at the members of the robotics team. “And by the way,” he inserted with a smile, “they also won first place.”

His message was clear: Sacred Heart School – Ateneo de Cebu may be known for its excellence in academics, sports, and the performing arts, but its priority – its mission – has been and always will be formation.

Forming the Regent

“The regency experience is different for everyone. But you tend to get the one that is most formative for you.” – Fr Joel Liwanag, SJ

Regency is the period in Jesuit formation after philosophy studies where a Jesuit is sent to an apostolic community for mission. In the Philippines, this mission is often in one of the Ateneos. The mission specifics depend on the needs of the school and on the strengths and weaknesses of the regent but more so on what is most formative for the Jesuit – what responsibilities and experiences will help form that person to be a good Jesuit. Thus, it is helpful for a young Jesuit to approach Regency with a sense of availability and trust: available for any assignment and trust in his superior that he has at heart what is best and most formative for the regent.

“Onstage.” Bro. Patrick introduces himself to high school students; Fr Manny Uy looks on. Photo by RJ Abellanosa.

When I arrived in Ateneo de Cebu and learned of my list of assignments – much of which was unfamiliar territory – this was certainly a helpful mindset. Among my responsibilities were: teaching Calculus (how do I make IPP[1] lesson plans?), supervising veteran teachers (shouldn’t it be the other way around?), and implementing the DepEd curriculum for senior high school (which was going to be run for the first time). A senior teacher commented, “Isn’t that too much for someone new?” To which the reply was, “It’s okay, he’s a Jesuit!” – as if I had superpowers I was unaware of. I was grateful for how much the school believed in me; but I honestly also felt in over my head. Trust in my superior was quickly accompanied by trust in my co-teachers and a very palpable trust in God’s providence.

And God did provide. For example, I was worried about supervising veteran teachers, some of whom were already coordinators in previous years. What could I really teach them? They could resent me. But as it turned out, they were actually glad to merely be teachers and focused on teaching, and to leave the paperwork, meetings, and other administrative roles to me. I was happy that my assignment allowed them to return to teaching, which was their passion.

Their joy and goodwill were beneficial in a roundabout way. Because I was new, those early weeks of teaching were difficult and very humbling. Even though I knew the subject matter well, my boardwork was all over the place and I had trouble managing the class. And the exams I made were too difficult which led to numerous complaints from students and parents. I needed help – and it was these veteran teachers (who felt good about not having administrative work) who encouraged me and took the time to sit patiently in my class to mentor me.

However, the biggest challenge was running the senior high program for the first time. There were so many operational details to work out: who was in charge of what? was it possible to insert a laboratory class? did we have enough space in the canteen? It was overwhelming. But then the Lord answered by sending good and able teachers and administrators. Not that they already knew what to do during those initial meetings, but there was a pioneering energy, a cooperative spirit, and a deep love for the school. We made lists and tackled problems one by one – and we got things going. We were far from perfect and there were many missteps and on-the-fly adjustments along the way, but we felt real consolation setting up the foundations for the school’s senior high.

Regency is a time to grow. It endeavors to push a Jesuit outside his comfort zone and towards his limits in the hope that he will grow and find himself. For someone accustomed to careful planning and organization, I had to learn to get used to walking on unfamiliar and shaky ground. During my regency, I often wondered how I could cope with the stress of pioneering work. But that was the beauty of availability and of simply saying “yes”. As with Mary’s fiat, when the Lord invited, He also provided much grace. And this was what I needed to experience and accept (and not just understand in theory): that for all the planting, tending, and worrying I did, it was really the Lord’s vineyard – it was His mission. And though I did not clearly see the plan, I could be at peace and trust that He will carry it through.

A Culture of Formation

“Every kid is one caring adult away from being a success story.” – Josh Shipp

My favorite time in regency was in the afternoon (especially when there was no meeting), around 4:30 when classes were over and the day was winding down. I left my desk and the piles of unchecked papers, headed down to the canteen, and simply hung out. There, I saw students relaxed and free, eating and lounging on the couches and benches. And we talked – about the new game they were playing, their Korean crushes, what stressed them in school, how they related with imperfect parents, what worried them about college, their desire for independence – anything and everything. No judgement, no agenda – we just enjoyed each other’s company.

The school invests much on important formation activities like retreats, outreach activities, and guidance programs. However, there is also real formation that happens when a teacher “wastes” time with students. Indeed, more than big events, it is (as the fox explained in The Little Prince) regular presence that is more meaningful and appreciated. “Wasted” time is really time well-spent.

It was edifying to see that many teachers had their own strategy to be with students outside class. Whether they arrived early and spent time in the classroom before the first bell or took recess and lunch with the students or set a schedule for one-on-ones – they found time to “waste” with students. This was the culture I found in Sacred Heart. So much so that teachers were more than teachers. They were also confidants, mentors, friends – and yes, second parents.

When teachers took the time to listen to students, to be interested in their dreams, to make them feel accepted, cared for, and loved, students could not help but grow and learn to love as well. The work of formation is complicated and the fruits are not immediately apparent. But it is worthwhile.

And what was true for students was also true for teachers. On my last day of regency, there was a short farewell program in the Pope Francis Hall. There, onstage, I was told that what my co-teachers most appreciated was not that I worked long hours or did strategic planning or even managed construction but that I often took the time to drop by their table and ask, “How are you?”

Showing the Way

“Good teaching cannot be reduced to technique; good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher.” – Parker Palmer

In the course of teaching Calculus, there came a moment when a good number of my students were faced with a wall – when they felt that even with hard work, the lessons were just beyond comprehension. It was demoralizing for the students, and for the teacher. I showed them more practice exercises and offered remedial classes, talked about grit and perseverance, even highlighted industry applications – but none of it worked.

Nothing seemed to help, until, in an unplanned moment, I talked about my own struggle learning Calculus: that I started out lagging behind my classmates and needed to catch up, that I did poorly in my first exams, and the hours and hours I spent on problem solving – so much so that I had Calculus in my dreams. It was tough but I did not give up until I got it.

If it was possible for their teacher to struggle and learn Calculus, they must have thought, then it was possible for them too. I told my classes that I knew the subject was very hard, and it was really up to them if they will persevere or give up. “You may give up, you may not – that’s up to you,” I said, “but I’m not going to give up on you.”

More than the well-prepared lectures and activities, it is the person of the teacher that students really look at and learn from. The hope is that students will learn grit when they see grit, and they will believe in themselves if someone believes in them. The same goes with other virtues, like patience, discipline, and trust in the process.

Students follow the example of their teachers – and of their parents, and of the adults they see. That explains why public figures and those in position, even if they do not claim to be role models, are still very influential to young people. By what these adults say and do, they define what is acceptable and normal. And we do not need to look far to see the effect of this today.

Thus, if a public figure is dismissive of God and relies only on his own power and authority, then it is important for students to see how their teacher humbly asks for help, is comfortable in uncertainty, and has a deep trust in God.

If a person in position promotes expedient and sweeping solutions that do not consider the devastating effects on people, then it is important for students to see how their teacher takes the time to listen and care for them, and has the willingness to “waste” time to form each one.

If a prominent adult espouses vice and hate and has a penchant for putting others down, then it is so important for students to see how their teacher loves them, believes in their capacity to overcome obstacles, and very much wants them to succeed in life.

It is the task of teachers to show a better way. And teachers in Sacred Heart are able to do so because they draw inspiration from the greatest of teachers who shows the best way.

In the school chapel, there is a lovely image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. It depicts Jesus gently holding out his torn and wounded heart with arms outstretched, offering it to the viewer. It shows a person who has given all in love, has been deeply hurt, but is still very much willing to love – over and over again.

“The Sacred Heart.” Image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus by Pompeo Batoni, located in the Church of the Gesu, Rome.

The Way of Christ is love. It is a love that forms and transforms.

When I get to ask the veteran teachers in Sacred Heart about their greatest joys in teaching, I am not surprised anymore to hear stories of their students – old and new – who have bloomed in life: students who not only excelled in academics, sports, and the performing arts (or in career, profession, and business), but have also selflessly used their gifts to help, serve, and love others.

[1] Ignatian Pedagogical Paradigm. This special format is the hallmark of all lessons in an Ateneo classroom.

Sch. Joseph Patrick Echevarria, SJ taught at the Senior High School Department of Sacred Heart School-Ateneo de Cebu for two years (2016-2018). He is currently on his 1st year of Theology at Loyola School of Theology, Ateneo de Manila University.

If you’re interested to join the Jesuits, please join our vocation seminar on September 23, 2018, 8:30am to 4:30pm at the Loyola House of Studies. You may contact 0917-JESUITS (0917-5378487) or email at vocations@phjesuits.org.