This article appeared in Windhover, February, 2014. Written by: Jenny Lyn Lee

A Jesuit-run indigenous school in Bukidnon

The Apu Palamguwan Cultural Education Center (APC) is a Jesuit-run, DepED-recognized elementary school for indigenous children nestled in the mountains of the Pantaron Range, in the Bukidnon-Agusan border. APC is located in a small indigenous village of 60 families called Sitio Bendum, of Barangay Busdi, Malaybalay City. Bendum is a four-hour bus ride and a 30-minute motorcycle ride away from downtown  Malaybalay.

Malaybalay.

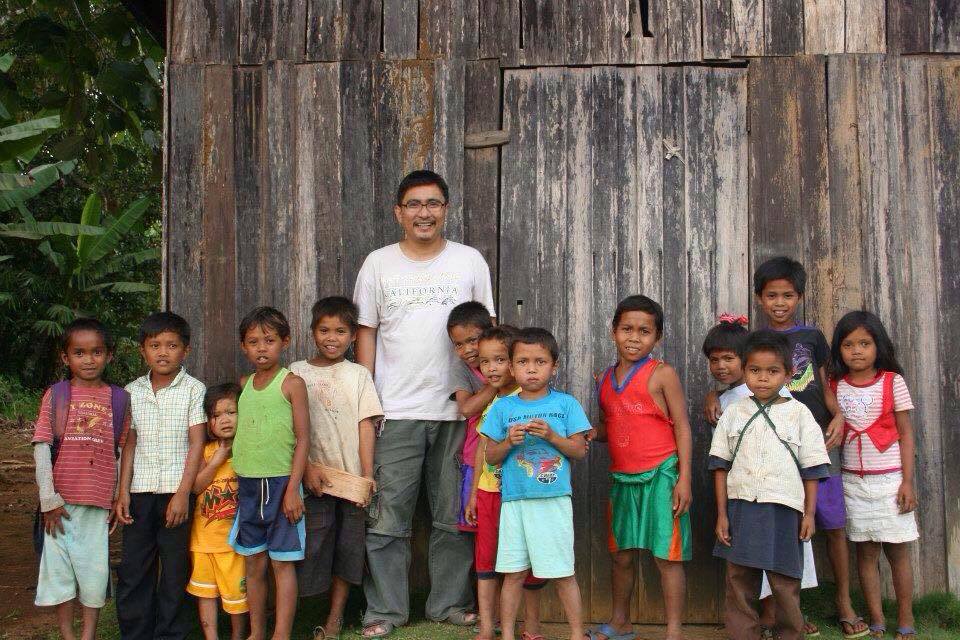

This school is a work of partnership with the Pulangiyen people of Bendum. The Pulangiyen are one of the indigenous groups of Bukidnon, and as traditional, they identify themselves by the river system that they inhabit, the Pulangi River. The APC school serves 120 children in Bendum and 60 more in an extension school in nearby Sitio Nabawang, which is also a Pulangiyen village. Children from villages further away-also come to study at APC in Bendum and are housed in a dormitory within the school complex. APC teachers mostly come from the Bendum community and are therefore Pulangiyen.

This school is a work of partnership with the Pulangiyen people of Bendum. The Pulangiyen are one of the indigenous groups of Bukidnon, and as traditional, they identify themselves by the river system that they inhabit, the Pulangi River. The APC school serves 120 children in Bendum and 60 more in an extension school in nearby Sitio Nabawang, which is also a Pulangiyen village. Children from villages further away-also come to study at APC in Bendum and are housed in a dormitory within the school complex. APC teachers mostly come from the Bendum community and are therefore Pulangiyen.

Recently, APC has started to organize classes in other small villages that are far away from public schools. The effort is to respond to the need for education in these indigenous communities that are not reached by government services.

Humble beginnings

The partnership with the Pulangiyen people began in 1992, when the community of Sitio Bendum requested Fr. Pedro Walpole, SJ to help them set up a school. As then Assistant Parish Priest at the Jesuit parish of Barangay Zamboanguita, Pedro often walked to the surrounding villages to get to know the indigenous peoples better.

The partnership with the Pulangiyen people began in 1992, when the community of Sitio Bendum requested Fr. Pedro Walpole, SJ to help them set up a school. As then Assistant Parish Priest at the Jesuit parish of Barangay Zamboanguita, Pedro often walked to the surrounding villages to get to know the indigenous peoples better.

The people of Bendum were then in the midst of asking the government to send them a teacher. After complying with the given requirements—conducting a community census and building a makeshift schoolhouse—they still received no teacher. Government could not respond to their need because they were too few and too far away.

Pedro and some young volunteers he recruited began to organize literacy classes with help from a few local volunteers. Within three years, they were developing a full-fledged elementary curriculum, with mother tongue as a subject and as language of instruction in the lower grades. Cultural knowledge and local community concerns were also incorporated in the curriculum. After a few more years, the school began initiating a dialogue with DepED to have this alternative approach to educating indigenous children be recognized. The advocacy continued until the early 2000s and APC received its official recognition in 2005.

Grounding in Cultural Identity

Right from the start, classes in Bendum were taught in the mother tongue. At first, this was because the community wanted their children to learn a practical literacy and numeracy that would be useful for community life. Later, as the engagement with the community developed, the people of Bendum began to articulate the value they place on cultural identity and saw the school’s use of the mother tongue and its teaching of cultural knowledge as integral to sustaining this identity.

It must be said that the Pulangiyen identity is a recently resurfaced identity. In the past, the people of Bendum identified themselves simply as lumad, a generic term for indigenous peoples in Mindanao. Like other indigenous groups, they generally felt a sense of shame in being identified as lumad. They felt inferior against the Bisaya, migrants who came from the Visayas, rarely spoke in community meetings, which the Bisaya dominated, and shied away from lowlanders. They considered their language and culture as inferior to the language and culture of the migrants and of mainstream Filipino society.

Historically, indigenous peoples retained their cultural identity by refusing to be assimilated in the new social orders brought about by the Spanish and American colonizers. However, refusal to assimilate meant being pushed to the fringes and driven up to the mountains where they had to contend with increasingly unproductive land, limited access to health and education services, and on the whole, being marginalized from the wider political and economic process.

All these have given many indigenous groups in Mindanao a sense of inferiority and a view that their culture is outdated and that their language does not have value. It is the same in Bendum. Through the years, because of the continued use of the mother tongue and the teaching of cultural knowledge in the school, this sense of inferiority has gradually reversed. Because the mother tongue is used in school, the message that both adults and the young are getting is that the mother tongue is important and is valued. Now, children and adults alike speak the mother tongue proudly in the community. They now expect visitors and outsiders to learn their language, instead of them accommodating the latter by speaking Bisaya.

The community’s cultural practices are also alive, instead of being relegated as lessons in Social Studies, and even cultural history is passed on to the next generation. Recent years have seen a shift from the generic lumad identity to a more specific and more reflective Pulangiyen identity. The youth of Bendum now proudly identify themselves as Pulangiyen, in contrast to the sense of shame in being identified as a lumad only a generation ago. Some APC graduates who have gone down to study in the lowlands sometimes tell Pedro, “When we are in the lowlands, we do not have identity. But when we’re up here in Bendum, we have identity. You have given us identity.”

Wisdom in Cultural Knowledge

In Science class, APC students compare their people’s farming methods, which allow land to lie fallow for a few years and thus naturally recover its fertility, with those of the migrants’, which involve permanent and intensive agriculture that rely heavily on chemical fertilizers and pesticides. In Social Studies class, they study the indigenous political system and compare this vis-à-vis the local government system such as the sitio and barangay. In the lower grades, young children listen to folktales, instead of Western fairy tales, and learn the cultural values in these stories.

In all these, APC students learn that there is much knowledge and wisdom in their culture. They learn that not all knowledge comes from books, and that their parents and the community’s elders are important sources of knowledge. They learn that their way of life is neither outdated nor inferior. It is, in fact, valuable, not only because it is theirs and because it ties them to their forebears, but because it continues to be relevant as they grapple with the challenges their communities face today.

In recent years, for example, a deeper meaning to the word “Pulangiyen” was discovered. While this literally means “of the Pulangi River”, their name also comes from the word pulang, which is a historical cultural practice of resolving conflicts. This custom involves disagreeing parties to keep vigil, only going to sleep once a resolution has been achieved.

Historically, the Pulangiyen People were known as “bearers of peace.” They refused to take part in the ethnic wars common in olden days and provided a sanctuary to those orphaned and widowed by these wars. They gathered the datus of different settlements and brokered a peace agreement that laid out laws and customs about how the communities could live together in peace. This is what it means to be a Pulangiyen, to be a bearer and broker of peace.

In the midst of the present lack of peace in the area that surrounds Bendum, the Pulangiyen people has rediscovered a cultural value and practice that can guide their action. Rebel and military clashes continue in the area and these often leave communities in a state of fear and uncertainty. Indigenous youth are often drawn into the fighting as they are recruited by the two opposing sides. The Pulangiyen identity of being bearers and brokers of peace teaches Pulangiyen youth that there is an alternative to violence and armed clashes. It also challenges them to bearers and brokers of peace themselves in their own lives and communities. The practice of pulang teaches them a practical way to make this happen.

Thus, Pulangiyen youth and children are learning that there is much wisdom in their culture, wisdom that provides answers even to the challenges of today. This is significant because mainstream Philippine education and society are generally oriented towards the West. We learn Western values in school and in the media and we begin to think that all answers and expertise come from the West.

Culture-based education programs such as APC show us that there is a wealth of knowledge and wisdom in local cultures and languages. Cultures grow and change over centuries as people struggle with the questions of how to survive, live with others, and find joy and meaning in their lives.

Local cultures thus contain the accumulated wisdom of our forebears and it would do us good to mine them for knowledge as we grapple with the issues we face today.

Community Empowerment Over Individual Achievement

APC seeks to form its students for community leadership. We want students who are engaged with what is going on in the community, and students who will remain in their villages after high school or college, instead of getting jobs in the city. In Social Studies class, APC students tackle different community concerns, such as land security and peace and order, and learn about how these concerns are being addressed. Older students participate in village committees such as the one on water and forest. When a local concern crops up, such as a suspicious soil sampling in the village by outsiders (e.g. by a prospective mining firms), teachers and students take the lead in addressing the matter and seeking a resolution.

The focus then is on how APC students can help their people and their community, and how they can help protect and manage their gaup, the domain or area in which they live.

The Gaup as the Sphere of Environmental Care

For those of us who live in cities and therefore do not interact much with nature, the environment can seem like an abstract, intangible reality. For the Pulangiyen people, though, whose livelihood is mainly resource-based, the environment is a day-to-day reality. The gaup in which they live, with its forests, farmlands and bodies of water, is their experience of the environment. It is thus within the context of the gaup that APC teaches its students about environmental management and how to care for the land, water and life of the area.

Because indigenous peoples live close to the land and to the forest, traditionally, they have had good relations with the environment. They pay respects to the Migbabaya, Creator of all things, and to His spirit guardians in the water, land and all living things. They conduct prayer rituals when farming and ask permission before beginning an important task. The whole attitude is one of respect, a recognition of a Creator and an awareness that one is part of this whole creation. And because their life is heavily dependent on natural resources, the Pulangiyen know how to farm and extract resources without depleting the land and the forest.

This way of life, though, was disrupted by the entry of corporate logging operations in the 1960s and 1970s. The logging company also brought migrants from the Visayas, who stayed and eventually dominated local politics and the local economy. The migrants eventually gained ownership of much of the fertile lowlands and brought with them their permanent agriculture practices.

Since Pedro and his team began working with the people of Bendum, trees have been gradually replanted in the village. Through the school and various efforts in the community, Pulangiyen children are again growing up with an awareness of how important the forest is and how the way land is used can impact the environment.

Other longstanding efforts include the protection of the community’s water source and assisting the forest to regenerate naturally. This is done by by tending to wild saplings, planting endemic tree species and maintaining the area through regular brushing and weeding. This approach to regenerating forests, which is different from the traditional massive planting of trees in an area, is also practiced in other parts of the world. APC students and the youth of Bendum are involved in these activities which all revolve around taking care of the different aspects of the Pulangiyen gaup – the water, the land, and the forest.

Beyond these practices, there is an effort to teach Pulangiyen children about the ecological services that an upland forest community such as theirs provide to people in the lowlands and to the global community. APC students learn that the Bendum forests absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and thus help mitigate global warming. They learn that their responsible land use helps prevent soil erosion and landslides down the valley, and contributes to generating hydropower for Bukidnon by preventing the build up of sediment in the river system.

Guiding Pulangiyen children in practical initiatives and in gaining a greater scientific understanding are important, but these must be grounded in developing in them the basic sense of respect and gratitude for the environment and for the Creator who provides for them. It is from this sense of the sacred fostered in indigenous spiritual practices that we seek to teach our students how to better care for the land, water, and life in their gaup.

A Life-Giving Engagement

Visitors to Bendum sometimes remark at Pedro’s commitment to the Pulangiyen and see this as him having given so much to the people. But Pedro says, “I get as much life from them as they get from me.” I suppose this is what happens when you take the time to encounter people, to listen to them and learn from them, and journey with them as they seek a better future for their land, culture and children.

——————————-

Originally from Davao, Jen was first introduced to Fr. Pedro Walpole,SJ and the APC when she was assigned to Bendum as a Jesuit volunteer of Batch 22 in 2001 after graduating from the Ateneo de Manila University. She has since also studied Martial and Family Counselling at the Center for family ministries and is currently Program and Communications Facilitation Manager of the APC.